Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR

One of the most fun, or most exasperating countries, to analyze politically depending on your perspective is the perpetual also-ran known as Argentina. There is always a steady of stream of news, appointments, alliances, bills, elections such that it certainly is never boring. On the other hand, it produces total incomprehension in foreigners after a certain time: “Why is it that this country, which has everything (food, water, land, resources, educated people, safe borders) continues to crash and burn every ten years?”

That is the 1m peso question. Decoding Politics has extensive experience with the country, having been a regular visitor for the past two decades of dysfunction and cheap beef. We once read it described it as a ‘seductive, but structurally unstable country’ which we think is perfect. It seems like a real country, with well dressed people and nice architecture and functioning infrastructure, yet constantly does things that real countries would find inexplicable.

We are going to, in this piece dive a little bit in to the features as to why Argentina has so many infamous political and economic crises in the past decades. We’ll look at where we are now. And we’ll see if we can get an answer to the original question- will this craziness ever end?

A Crisis Each Decade

The last few Argentine crises listed in reverse order…….the list of major meltdowns is quite impressive.

2019: Alberto Fernandez + Christina Kirchner elected, stock market crashes and peso collapses. New IMF agreement negotiated in 2021/2 to keep the lights on.

2011/12: Argentina refuses to pay its US law debt and a multi year court battle ensues. It was ultimately settled under President Macri in 2015.

2003: Nestor Kirchner is elected and terrorizes business and the opposition. In 2007, and again in 2011, his wife Christina Fernandez de Kirchner runs and wins. Nestor dies of a heart attack in 2010.

December 2001/ January 2002: The famous crash of the burn of the peso and major default. Argentina has four presidents within a month.

1990/1: Hyperinflation and Afonsin elected President.

1982: Falklands Island war with UK. Argentina loses. The government collapses and the military decides to open up to democracy in time.

Argentina and its cynicism

The institutional failure is so complete, you would excuse Argentines for being a bit cynical about their country, their leaders, and their systems. Many of the most talented have left over the past thirty years, and millions more remain in a state of terminal apathy and disconnection from the government.

A recent Twitter thread perfectly captures how fed up and cynical the Argentines are about their own country and government. The incoming US ambassador (naively) posted a greeting to Twitter:

Such a naïve tweet exposed himself to Argentines and their savage cynicism about their own country. Replies included (in English and Spanish) “Don’t take the job, it’s a trap!” to “Please invade us, we will offer no resistance, just send our leaders to Guantanamo” and “Take the post of being Ambassador to Ukraine, it will be more quiet” among hundreds of similar comments. Argentines are so used to institutional failure and disaster that they can joke about it in the broadest of terms. Those not used to this Jurassic Park must find it quite surreal.

The System and the Legacy of Peron

On paper, the Argentine system resembles that of the United States. There is a President elected on a four year cycle, with broad powers. There is a Senate and Congress, the latter turning over every four years, the former every six. There are, including the City of Buenos Aires, 24 provinces, and their governors have been delegated a wide array of powers. The Constitution has been around since the 1850’s without much moderation.

Yet, behind the scenes, the Argentine system works very differently, having been constructed along the lines of a fascist country in the 1940s and never dismantled. President Juan Domingo Peron, in power from 1946-1955, was the one to bolster a system that borrowed from Mussolini’s Italy. Peron’s admiration for the fascist governments of Europe is well known. Here is one quote courtesy of Wikipedia:

“Italian Fascism made people's organizations participate more on the country's political stage. Before Mussolini's rise to power, the state was separated from the workers, and the former had no involvement in the latter. [...] Exactly the same process happened in Germany, that is the state was organized [to serve] for a perfectly structured community, for a perfectly structured population: a community where the state was the tool of the people, whose representation was, in my opinion, effective.[51]”

Source: Wikipedia

The government set up labor boards that controlled the major unions and bossed around the large employers in the country. Labor unions had wide ranging abilities to negotiate contracts and collective bargaining agreements, giving workers little say and corporations little control. The politicians who worked with the unions handed out money to them and got a guaranteed supply of votes.

Peron then threw tons of handouts to workers- he instituted and expanded a national health care system, giving three quarters of Argentine workers ‘free health care’. He expanded social security coverage to most workers. And he led two five year plans to industrialize the country and move it away from its dependence on agriculture.

Initially, the plan worked- real wages grew substantially and workers were fully employed. The country’s economy expanded into new industries. Yet by the early 1950’s, the peso was devaluing, the economy was facing 50%+ inflation, and Peron had to go abroad to get dollars to keep the lights on. He pushed a new Constitution in 1954 allowing for social grants to be enshrined, and to push for multiple terms for the President. This was all too much for the military, which pushed him out in 1955 and into exile.

The Ghost of Peron

If you look at the cycle of Peron’s two terms, it is very similar to the one that plays out in ten year increments in Argentina. A burst of growth from a low base, and an expansion of real wages. This rising prosperity is then used by the government to guarantee more spending and benefits to the working/voting classes. The spending gets too far ahead, the government runs out of dollars for some reason, and it all ends up in inflation and or default. Then cue a right wing government or the military to come in and clean it up.

The crises were often so extreme that they needed extreme measures to address them. Argentines who saved in dollar bank accounts have several times seen their dollars confiscated to pay debts or forcibly converted, at disadvantageous rates into pesos. Many times the government has banned or limited sending money out of the country. Gold as an investment was banned at one point under Nestor Kirchner. This total disrespect for the rule of law has seeped into all fields of economic legislation, allowing the government to run roughshod over political opponents and thoroughly discouraging investment in the country.

Peron’s party, the PJ, continues to have a strong power base in Congress, and it or its allies have held the Presidency for sixteen of the last twenty years. The four year term of Mauricio Macri (2015-2019) saw a heroic effort to extirpate the Peronist model, but they did not have the requisite time to clean up the mess, and were handed an electoral defeat after a steep recession.

Argentina under Alberto and Cristina

President Alberto Fernandez and Vice President Cristina Kirchner

With President Alberto Fernandez and Vice President Cristina Kirchner, we are right back into the Peronist model. The government was elected in 2019 and quickly moved to restructure the outstanding debt. The government has been spending money heavily, defaulting on various other debts, seeing the peso devalue heavily, and facing high inflation of 50%.

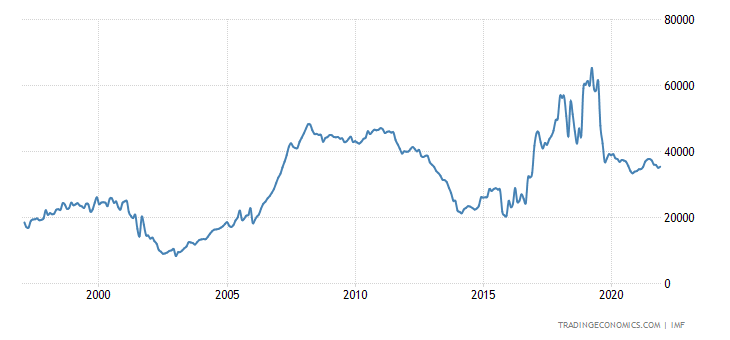

Argentina Inflation Rate , yoy %

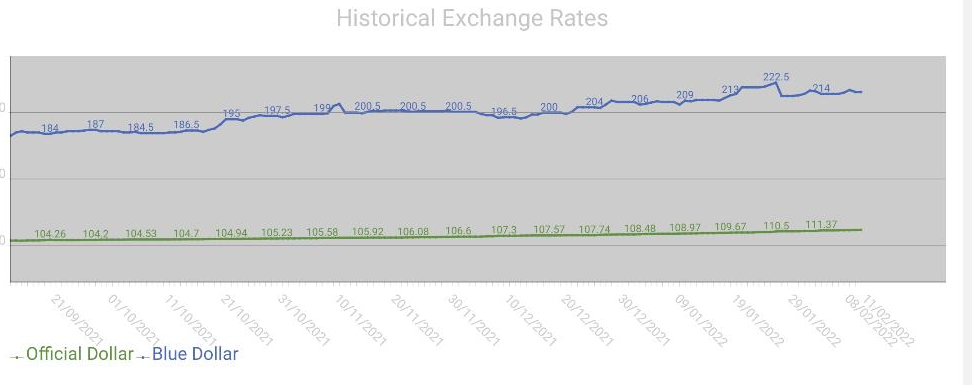

Moreover, the country has had to enforce a two tiered exchange rate system in order to keep inflation from totally blowing out. If you were to arrive in Argentina tomorrow and hit the ATM, you would get the official rate of 110 pesos to the dollar. Your $100 withdrawal would get you 11,000 pesos to spend. Yet if you were to take $100 in cash, and switch it on the street at the so called “Blue Dollar” rate, you would have 22,000 pesos to spend. The gap between the two is producing all sorts of distortions for the layman and arbitrages for the connected. If the unofficial and official were to reach parity though, it would produce another round of high inflation. So the government is caught between a rock and a hard place here and is unlikely to resolve it prior to the 2023 elections.

Source: dollar blue app

The country has been bleeding dollars over the past few years. On a gross basis, it has $35bn in reserves, but it is at its lowest level of dollars ever on a net basis of roughly $500m.

Argentina International Reserves, $mm

With lots of international debt payments coming due in the next year, it seems inevitable that Argentina will hit the wall again in some way. Either a default, a total peso blowout to finance this, or another series of restructurings. The Peronist model is allergic to austerity and lowering inflation, as that would see union support drop away immediately. They have to keep spending, printing money, devaluing the currency and blame the US/IMF for the mess. If the electorate believes it, they can get re-elected in 2023 for yet another four year term. If not, then it will be a right wing government’s turn to clean up the mess again.

The Players in 2022

Alberto, Cristina, and Maximo

President Alberto Fernandez is a main line Peronist, and had been Nestor Kirchner’s chief of staff. He is viewed as the peacekeeper between the various factions of government. Cristina and her son Maximo, leader of the faction called “El Campora”, are viewed as radical Peronists, but can routinely be counted on to deliver 30% of the electorate, mainly due to the number of handouts they had implemented to lower classes.

The government initially adopted a radical economic platform -restructure foreign debt, spend money, and toss out several Macri era reforms. Inflation and currency weakness were irrelevant. Yet as inflation ripped over 50% and dollars ran to nearly zero, the government was forced to change trajectory. They went to the IMF to renegotiate a deal and secure more dollars in exchange for a new government spending plan. After a deal was struck, it would then go to Congress for a final vote.

Yet this initial deal produced division. Alberto thinks it’s clearly needed. Cristina believes the terms are not fair. And Maximo thought it was poorly negotiated, and resigned his post in the government in protest, promising his followers would never support it. Now the government will have to renegotiate and hope to have enough of its followers to support it, or it will have to reach out across the aisle and work with the opposition to get a bill passed. Either remedy shows extreme division within the current government. The mounting economic pressures are seeing the coalition fray and its three main leaders work against each other.

The Peronist Party

The core Peronist party still has a substantial showing in Congress, over 25%. Several of its members are ministers in the government, often at odds with the Kirchner family. They have been flummoxed by the recent events. Many of these legislators want lower inflation and a steady economic environment. Not for its own sake, but so they have more money to bestow on labor, workers and political allies. They have no problem with high inflation if it’s coupled with high growth and a semi-stable currency- as happened between 2003-2008. But the current stagflationary mess with no end in sight is bad for business. They have been increasingly courting Alberto and trying to distance themselves from Cristina and Maximo Kirchner.

The Opposition – Juntos Por El Cambio (JxC)

Formerly Cambiemos, this is Macri’s party under its new name. It has three or four leaders, but the most prominent is former Buenos Aires province governor Maria Eugenia Vidal. She is a Catholic, an economic conservative, and a charismatic speaker. She was elected as a Congresswoman in 2021.

Maria Eugenia Vidal

The party is conventional center right party, business friendly, focused on law and order. They got Macri elected in 2015, and did very well in the 2021 legislative election [more below]. They are clearly going to take over Congress in 2023, and likely the Presidency, but the only question is by what margin. And, what allies will they have along the way?

JxC had a good run of reform under Macri, cutting all sorts of government programs, reforming the exchange rate system and initiating structural reforms. But they borrowed too much money in dollars, got into a bind, and had to call in the IMF. This decision and the resulting austerity cost them the 2019 election.

It is crucial that if they are re-elected, they enter power and enact structural reforms and belt tightening at the beginning. They should not borrow heavily and risk another exchange rate crisis. They should try to continually generate excess foreign reserves, and use that to gradually merge the exchange rates and to lower inflation. Finally, they will need to open up the labor market. Ending the unions’ hold on Argentina is crucial to ending Peronism’s political hold. If they can end collective bargaining, allow limited independent contracting and freelance work, and remove government labor boards from decision making, it will spell lower inflation all around and the end to Peronism’s control mechanisms.

The Farmers

The great silent player in all this, and has been for one hundred years, is the farming community. Argentina is an incredibly potent player in agriculture, and the industry earns almost 60% of all foreign currency in Argentina. The farmers are so profitable that they can endure 30-40% excise taxes without losing money. Argentina produces one quarter of global soy production- an incredible number for a country of less than 50m people. Argentina has huge production globally of lemons, sunflower seeds, beef and other categories. Indeed, the only reason Peronism exists in the first place is that Argentine farmers make so much money that the Peronists can distribute the excess to the 80% of the population not working in agriculture. Other countries without such an oil or agricultural surplus would be unable to generate the requisite revenue in the first place.

The Nestor and Cristina Kirchner administrations waged war on farmers, taxing them heavily, restricting their access to foreign exchange and imported goods, and often silenced them politically. But they still need them to generate dollars for the country and to keep people employed. It’s a difficult balance- you need the piggy bank intact, but you are constantly taking money out of it. This current domestic environment is very hard on farmers, and we think that if they lower the crops planted and amounts sold abroad, it will harm the government finances. The opposition has always been very friendly to farmers and so they are patiently waiting for a JxC government.

The Last Election

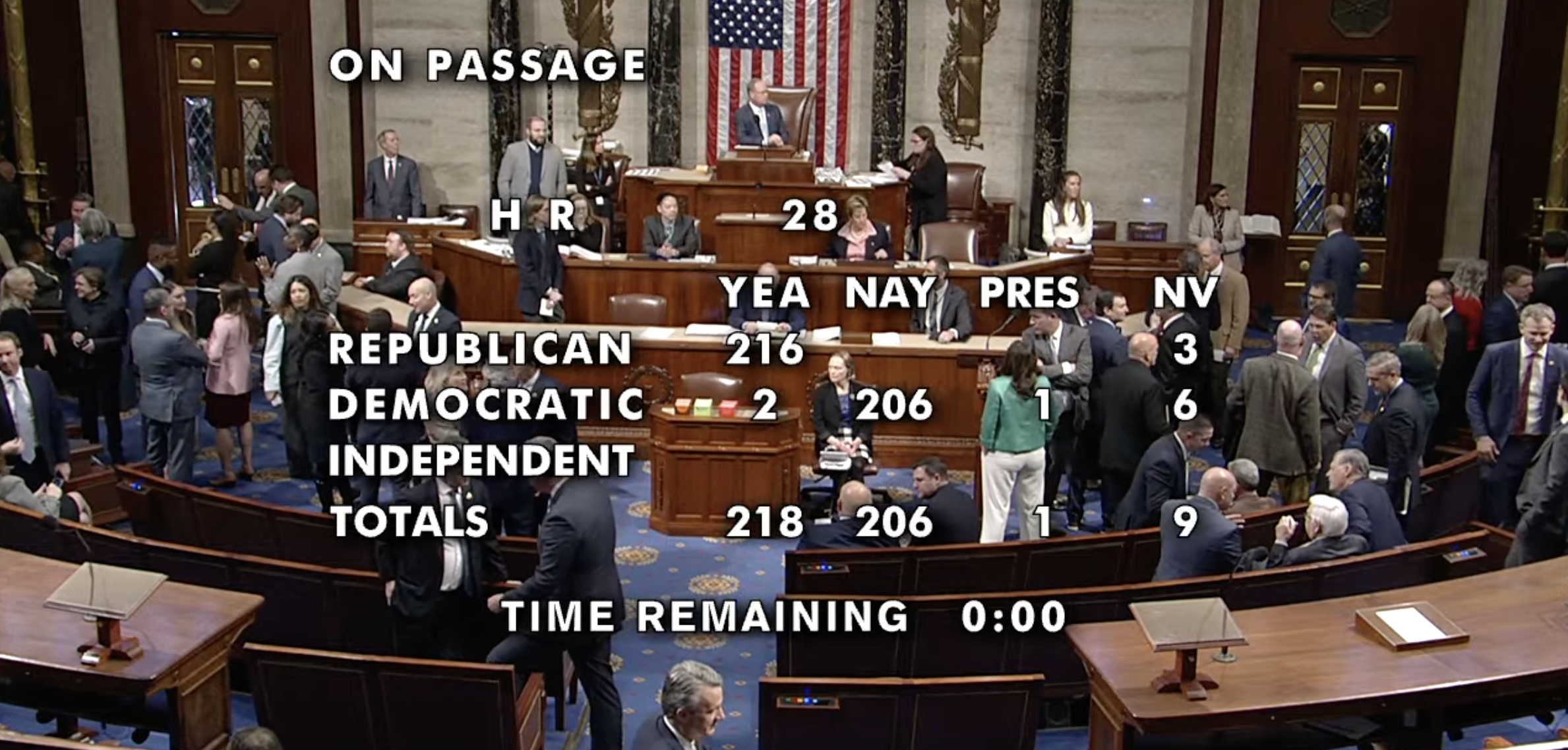

Argentina had a legislative election in October 2021. Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) had their best performance ever, taking 42% of votes for Congress and 47% for the Senate. The Peronists lost control of the Senate for the first time in 40 years. Libertarian and other opposition parties performed well, a first in Argentine political history.

This was Peronism’s worst election in decades, and the defeat means Congress can effectively block most legislation from the government. It augurs well for a large election victory in 2023.

The Outlook from Here

Argentina’s Presidential and Legislative Elections will be held October 2023. It will be yet another historic confrontation between Peronism, represented by Alberto Fernandez and Cristina Kirchner, and the opposition of JxC. Peronism will be entering at a serious disadvantage. The coalition is full of internal dissent and conflicts. It’s coming off of a bad election loss. And the economic fundamentals are pure stagflation, with downside risks from a currency that continues to crash, and a government with no dollars to defend it.

It is likely that JxC wins, with Vidal as its public face. From there, they will have the usual clean up to perform. Cut government spending to below the rate of inflation. Merge the exchange rates over time, and take the initial pain but hope inflation comes down over time. Do structural reforms to open up the economy to foreign investment and competition. Finally, they will have to enact a broad labor reform. Ending union power and government handouts to unions is the only way for Peronism’s political power to fully wither away. Otherwise, each economic boom that Argentina stumbles into will just see the money distributed to voters and political allies rather than saved, wisely invested, or remain in the hands of entrepreneurs and farmers. The jury is still out if the next election will finally end the 70 year Peronist cycle of crash and burn. The ruling coalition of half Peronists half radical Peronists is weak and rife with infighting. Popular discontent at a decade of almost 50% annual inflation, slow growth and government corruption is building. The opposition’s political gains have been strong and should extend into 2023, giving them a broad mandate to enact major reforms. The jury is still out if they will be able to kill the Peronist cycle and end the craziness, but the opportunity is better than it has been for three decades.

Follow Decoding Politics on Twitter: https://twitter.com/DecodingPoliti2

For Inquiries/Comments: [email protected]

Breeding tells. Genetics among a population reveal the most basic character of an organism.