China could display global leadership by being pragmatic, confident and relaxed about democracy for Hong Kong and Taiwan

TAIPEI: The ongoing protests in Hong Kong offer insights into China’s flexibility of governance and its patient ability to challenge the current world order. Much has and will be written on this issue. But for an answer on how governance may unfold, consider Taiwan, which for 70 years has stood in the storm’s eye of a hostile and suspicious China.

One conclusion being mooted through think tanks in Beijing and Taipei is that the most pragmatic way forward is for China to be confident and counterintuitive enough to grant Hong Kong full democracy. Such a move would take the wind out of protesters’ sails, extinguish flames of discontent and enhance China’s global standing while being no threat to its own system of governance. The identities of the think tanks and academics involved remain confidential, but this is their argument.

Hong Kong and Taiwan are both developed economies with highly-educated Chinese populations. Taiwan is a democracy. Hong Kong is not. Sovereign control lies with Beijing, although under the “one country, two systems” agreement between Britain, its freedoms, capitalist system and way of life are meant to continue until 2047.

The first major protests erupted in 2014 because voters were denied direct election of the chief executive. Instead a committee was created to favor Beijing’s choice.

The current protests were sparked by a law allowing extradition to China, but have broadened into a range of issues including police brutality, Beijing’s general interference in Hong Kong and the curbing of democratic freedoms. The extradition law itself has been withdrawn, but belatedly and only after sustained pressure from the streets.

One day of protest attracted as many as 2 million people. When more than a quarter of the population simultaneously takes to the streets, any ruler, dictator or democrat, should know they have a serious problem. Amid such mass discontent, identifying an endpoint is difficult. The think-tank advice is that Beijing, therefore, needs to jump several steps ahead and identify one that will meet broad, popular approval. The cleanest way would be to grant full democratic autonomy to the territory and, from Taiwan’s experience, fears that this would be a dangerous precedent are likely to be unfounded.

Of course, a major difference between the two is that, apart from a handful of islands, Taiwan has distance from the mainland as well as de-facto independence and a fully operational military designed to withstand a Chinese invasion. Nevertheless, like Hong Kong, it also reliant of China, not least for its trade which has given its citizens a high standard of living and turned it into a fully developed economy. The paradoxical relationship whereby China is both Taiwan’s biggest trading partner and most threatening enemy has developed in a steady trajectory over seven decades and is unlikely to change in the near future.

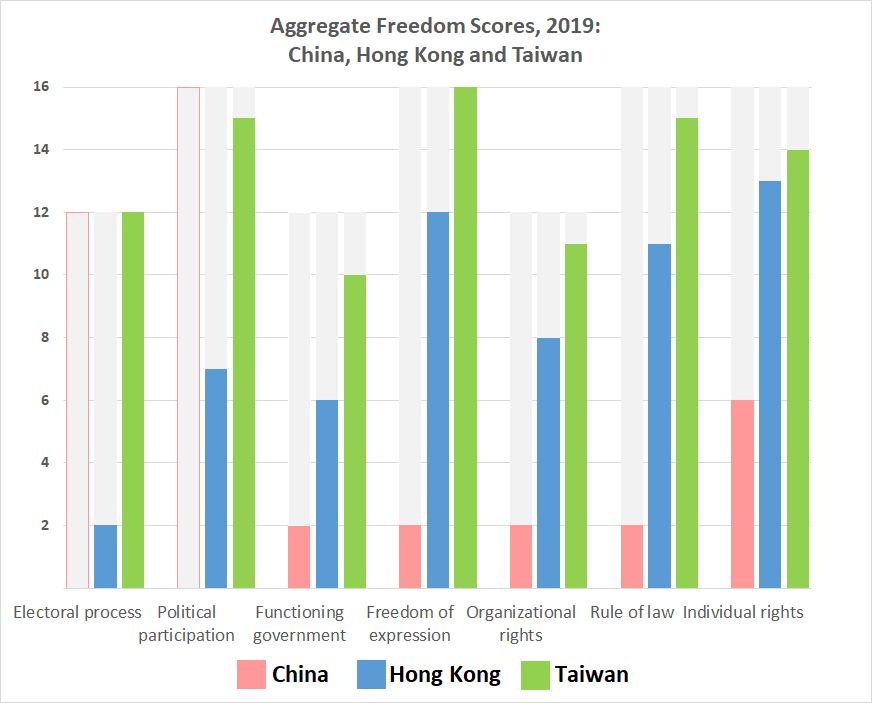

Layers of freedom: Freedom House assesses nations for democracy and scores China at 11; Hong Kong at 59 and Taiwan at 93 (Source: FreedomHouse.org Map 2019)

From 1949, when China’s defeated nationalist armies fled to Taiwan, to 1979, when the One China Policy came into force, Taiwan faced a real threat of invasion. During those 30 years, both China and Taiwan were weak and poor dictatorships. Only in the 1980s did reform begin with China taking steps to become an economic power and Taiwan preparing for democracy.

In 1996, as Taiwan held its first presidential election, the Chinese threat of invasion emerged again with military exercises and missile tests, such that the United States deployed a carrier group through the Taiwan Strait. The election was a success. From there administrations changed between the more pro-China Kuomintang to the more pro-democracy Democratic Progressive Party that is currently in office. The DPP first won in 2000. Beijing’s hostility and rhetoric again increased, not least because the founding policy of this now ruling party was to declare full sovereign independence from China. But once in power, hard-nosed political reality set in. The United States would not back any declaration of independence, and the new government needed to maintain some form of working relationship with China. The DPP shelved its independence plans and concentrated on improving voters’ living standards.

A similar political reality tempered the ambitions of the pro-China KMT party when it was last in office. In 2014, KMT drew up trade legislation which critics argued would make Taiwan vulnerable to Beijing. Protestors took to the streets and smashed their way through police lines into both the legislature and government offices. The new law was withdrawn, and the protests melted away.

Taiwan voters therefore have sent a clear message to the rival political parties that they want to be neither too far nor too close to China. During Taiwan’s more than 20 years of democracy, both it and China have flourished. Trade has helped both become rich. China has forfeited nothing on the world stage by losing this unrecovered sovereign territory to a rival ideology. What could have been war has been a win-win on both sides.

Should China allow Hong Kong direct elections for a chief executive, voters might well deliver a pro-democracy candidate to office. But, as with the DPP in Taipei, they would need to work and compromise with Beijing. The second election might well swing the other way with a pro-China candidate and so on.

Contentious issues on the school curriculum, police brutality and an independent judiciary would be dealt with in-house. Any lingering cries for independence and other impossible longings would fade under a popular wave of pragmatism. Regardless of who sits in Government House, Hong Kong’s unique selling point as a state-of-the-art financial trading hub would be retained. At present, this status is at risk.

Instead of Hong Kong’s new democracy acting as a contagion across the border, it could be used as an asset. Millions of Chinese now travel to Hong Kong, Taiwan and have been educated at Western universities. The concept of democracy and free speech is no longer strange. At some stage in the near future other Chinese regions with educated populations will push for more freedoms that no amount of facial recognition, riot police and nationalist slogans can suppress. Beijing could then draw on the Hong Kong experience to determine how much to loosen or control. Should this experiment work, it would also cancel the need for a sudden and probably unpopular readjustment leading up to July 2047 when, by law, Hong Kong loses its special status rights. Instead, relations could be maintained and there would be no reason to risk unrest.

Then, two years later, when the Communist Party celebrates a 100 years in power, Hong Kong could be platformed as a success story. This scenario, bouncing around academic circles, may or may not have been seriously examined by President Xi Jinping and his advisors.

The problem, of course, is that the end point could be a fully democratized China although that would be many decades if not another century away.

China’s aim is to regain what it sees as its natural position of world leadership but – unlike the the United States and Western colonial powers – without the wars, indeed without any shot fired in anger. Political change in a developing society is inevitable. The pressing urgency of Hong Kong, therefore, would be a good place for China’s leaders to start getting their strategy right.

Humphrey Hawksley, an Asia specialist, was in Taipei as part of a delegation of British think tanks focusing on defense and security. Originally published at Yale Global Online.