Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR, Truth Social

Reprinted with permission Jane Hampton Cook Substack

As people around the world mourn the death of Queen Elizabeth I, they also awaken to the reality of a new British monarch.

Hearing the name King Charles III for the first time struck a dissonant chord in me. I instantly thought of both the baggage he carried as Prince Charles and his namesake, the notorious King Charles I.

When Queen Elizabeth II became queen in 1952, she was a blank slate. At only 25 years-old, her political views, opinions, and preferences were unknown to the public. Her personal lifestyle was unimpeachable.

She was a married mother of two in the post-World War II era that revered family, God, and country. At the time, no one knew if she would live up to her namesake, Queen Elizabeth I, and rule with dignity or if she would become a polarizing political figure.

In contrast to his mother, King Charles III, age 73, is hardly a blank slate. Despised for his treatment of Princess Diana, he has also spoken out on controversial political issues, such as climate change, and has associations with the unelected, power-hungry World Economic Forum and its dangerous Global Reset plan. Unlike his mother’s namesake, King Charles III's namesake was a polarizing divisive king. King Charles I’s intolerance of Puritans and demand for theological infusion with Roman Catholics drove many English men and women to America’s shores.

The legacy of King Charles I was so significant and notorious, that it sparked a personal mini-Revolution in an American minister more than 100 years after the king’s death.

I wrote about this minister and King Charles I in my daily devotional book, Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Enjoy the adapted excerpt below.

The choice this pastor made in 1750 was as culturally acceptable as women wearing pants at the time. Not only did he breech the cultural taboo of not preaching on politics from the pulpit, but he also broke with the latest instructions from the Church of England.

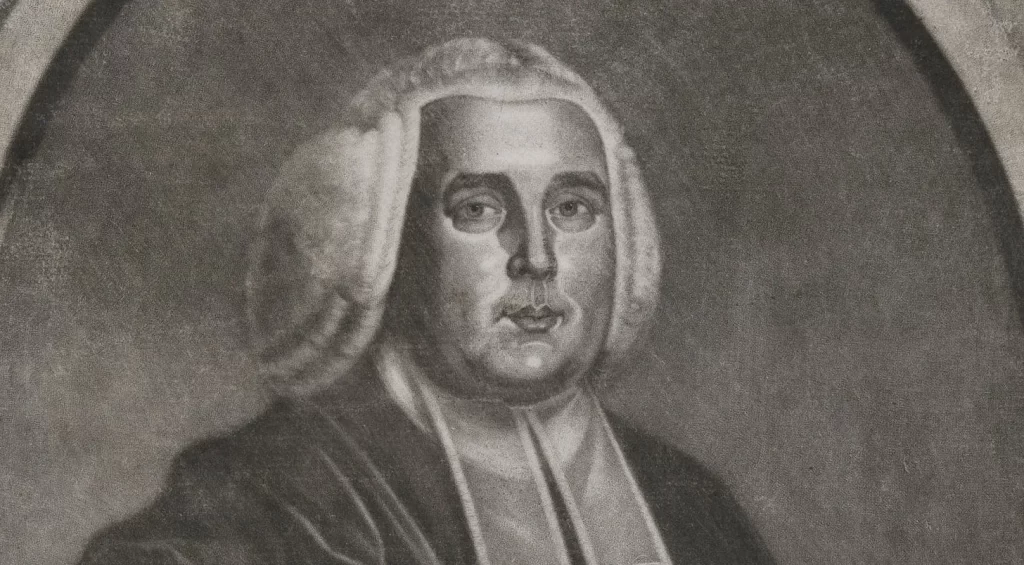

Thirty-year-old Jonathan Mayhew of Boston’s West Church faced a difficult decision. The Church of England was requiring ministers in both England and its American colonies to preach sermons praising King Charles I, who had died 100 years earlier on January 30, 1749.

Mayhew simply could not comply. Why not? Like many great-grandchildren of Puritans, to Mayhew, King Charles I was not a martyr to be revered. Instead, he was a tyrant to be reviled.

King Charles I ascended to the throne in 1625, following the death of King James VI and I, who had given Britons the King James version of the Bible. Like monarchs from the Middle Ages, King Charles I believed in the divine right of kings. Because God anointed the king or queen, the monarch must be obeyed. As a result, Charles believed that he could not be held accountable by Parliament.

King Charles I took the divine-right-of-kings belief too far. Charles believed that Adam was the first king and he was the current Adam ruling with the same God-given dominion. Divinity meant that Charles was near deity, an extension of God and thus, he was part divine.

King Charles I despised the House of Commons, which represented the people in Parliament. His many abuses included disbanding Parliament, enacting a Star Chamber to ensure monopolies for basic goods, imposing severe taxes, and ordering a “conjunction between” Catholics and Protestants in “doctrine, discipline, and ceremonies.”

This conflict led to the English Civil War. The people eventually fought back by trying and executing Charles I in 1649, dissolving the monarchy, and replacing him with Oliver Cromwell. When Cromwell died in 1658, Parliament reinstated the monarchy. The ascendant King Charles II made his father’s death a sacred holiday. The Church of England viewed the 100th anniversary of Charles I’s death as a very special occasion.

But Mayhew believed this “divine king” was far from a martyr. Charles I was more tied to tyranny than a lion was to its crowning mane.

The irony galled Mayhew. Forcing ministers to preach an anniversary message heralding Charles I was itself a form of tyranny.

“Tyranny brings ignorance and brutality with it. It degrades men from their just rank into the class of brutes; it damps their spirits,” Mayhew declared. He called ecclesiastical tyranny, “the most cruel, intolerable, and impious of any.”

Mayhew knew his decision to mix royal politics with religion from his Boston pulpit might be controversial to both bishops back in England and his congregation in Boston. He made it clear, however, that he was not “preaching politics, instead of Christ.”

He defended his decision by citing 2 Timothy 3:16, “All scripture . . . is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (KJV).

“Why, then, should not those parts of Scripture which relate to civil government be examined and explained from the desk, as well as others? Obedience to the civil magistrate is a Christian duty,” Mayhew told his parishioners.

Mayhew believed government was a moral and religious issue. After all, if private persons were required to yield to the authority of a monarch, then he could preach against a king’s tyranny from the pulpit.

Mayhew’s decision to speak out against tyranny and preach about civil government sparked something inside him. He began to preach other similar ideas from the pulpit. Eventually he became known as a radical minister, but his courage led other ministers to speak out against King George III in 1776 from their pulpits.

Likewise, Puritan philosopher John Locke countered Charles I and the divine-right-of-kings philosophy in his famous work, Two Treatises of Government. Believing that rights came from God and not government, Locke's phrase life, liberty and estate later became life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of independence.

Jonathan Mayhew was a bridge between Puritan America and Revolutionary America. He opposed the Stamp Act in 1765.

The American Revolution would not have taken place without voices from the pulpit helping their congregations navigate the treacherous waters of governmental tyranny and whether it was acceptable by their faith to take up arms against their king if he’d become a tyrant. They looked to the king of kings, not their earthly king, for ultimate guidance and authority.

PRAYER

Lord, thank you for reigning as the King of kings.

“He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the hearts of men; yet they cannot fathom what God has done from beginning to end,” Ecclesiastes 3:11.

Adapted from Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!