Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR

Reprinted with permission Mises Institute Ryan McMaken

If you did any Fed watching this week, you probably heard all about how Jay Powell has turned (or perhaps returned) to hawkishness, and how the Federal Open Market Committee is all about fighting price inflation now.

A particularly cartoonish version of this claim was written by Rex Nutting at MarketWatch, who declared, "Everyone’s a hawk now. There are no doves at the Fed anymore." He wrapped up with "This means that inflation no longer gets the benefit of the doubt. It’s been proven guilty, and even the doves will prosecute the war until victory is won. For the inflation doves at the Fed, Nov. 10, 2021, was bit of [sic] like Dec. 7, 1941: Time to go to war."

This reads like a parody, so I’m still not 100 percent convinced this writer isn’t being sarcastic. But one will find no shortage of articles making similar claims throughout the financial media—albeit in a less over-the-top fashion.

We’re told about the “Jay Powell pivot” and how the Fed will even soon be “normalizing.” Let’s just say I’ll believe it when I see it. In fact, the evidence strongly suggests the Fed is still of the thinking that only a few tweaks will set everything right again. All that’s needed is a slight slowdown in quantitative easing (QE), and maybe an increase of fifty or a hundred basis points to the federal funds rate, and happy days are here again.

In other words, the Fed is still thinking the way it has thought for the entirety of the twelve years since 2009, when today’s QE experiment began. In that view of the world, it’s never the right time to end unconventional monetary policy. It’s never the right time to sell off assets. It’s never the right time to let interest rates increase by more than a percent or two. Meanwhile, the reality for ordinary people has been one of the weakest and slowest recoveries in history. But the Fed justifies it all to itself because Wall Street is happy.

That’s been the reality for more than a decade. And there are no signs that the Fed is “pivoting” away from that any time soon.

Although the Fed exists in its own reality, there is no doubt that the political situation in the real world has changed. In spite of countless efforts by the administration and members of Congress to blame inflation on “corporate greed” and “logistics,” the less gullible among us know that monetary policy has had at least something to do with rising price inflation.

Even your average elected official—who knows nearly nothing about monetary policy or the Fed—is likely experiencing a very dim and slow realization that a decade of QE and money printing is one of the culprits. So, when Jay Powell’s on Capitol Hill, the politicians want to hear him say he’ll do something to fix inflation. We shouldn’t be terribly surprised when Powell and other Fed governors say that yes, they’ve got inflation in their sights.

But they have to say that. Last week, Consumer Price Index inflation hit a forty-year high, and rose at a faster rate than average earnings. Moreover, this week’s new Producer Price Index (PPI) data showed similarly bad numbers, with growth rates also hitting forty-year highs. For example, the PPI for finished goods less foods and energy hit 5.8 percent, which is the highest growth rate since 1982. Even worse, PPI growth is often an indicator of future Consumer Price Index growth.

Politically, that’s hard to ignore.

So let’s look at what the Fed says it’s going to do. According to Wednesday’s Federal Open Market Committee press release:

The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. In support of these goals, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent. With inflation having exceeded 2 percent for some time, the Committee expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee's assessments of maximum employment. In light of inflation developments and the further improvement in the labor market, the Committee decided to reduce the monthly pace of its net asset purchases by $20 billion for Treasury securities and $10 billion for agency mortgage-backed securities. Beginning in January, the Committee will increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $40 billion per month and of agency mortgage‑backed securities by at least $20 billion per month. The Committee judges that similar reductions in the pace of net asset purchases will likely be appropriate each month, but it is prepared to adjust the pace of purchases if warranted by changes in the economic outlook.

There are a few takeaways from this, none of which suggest any radical departures from the status quo.

The first is the Fed is still very much wedded to its totally arbitrary, made-up, and novel notion of maintaining 2 percent inflation.

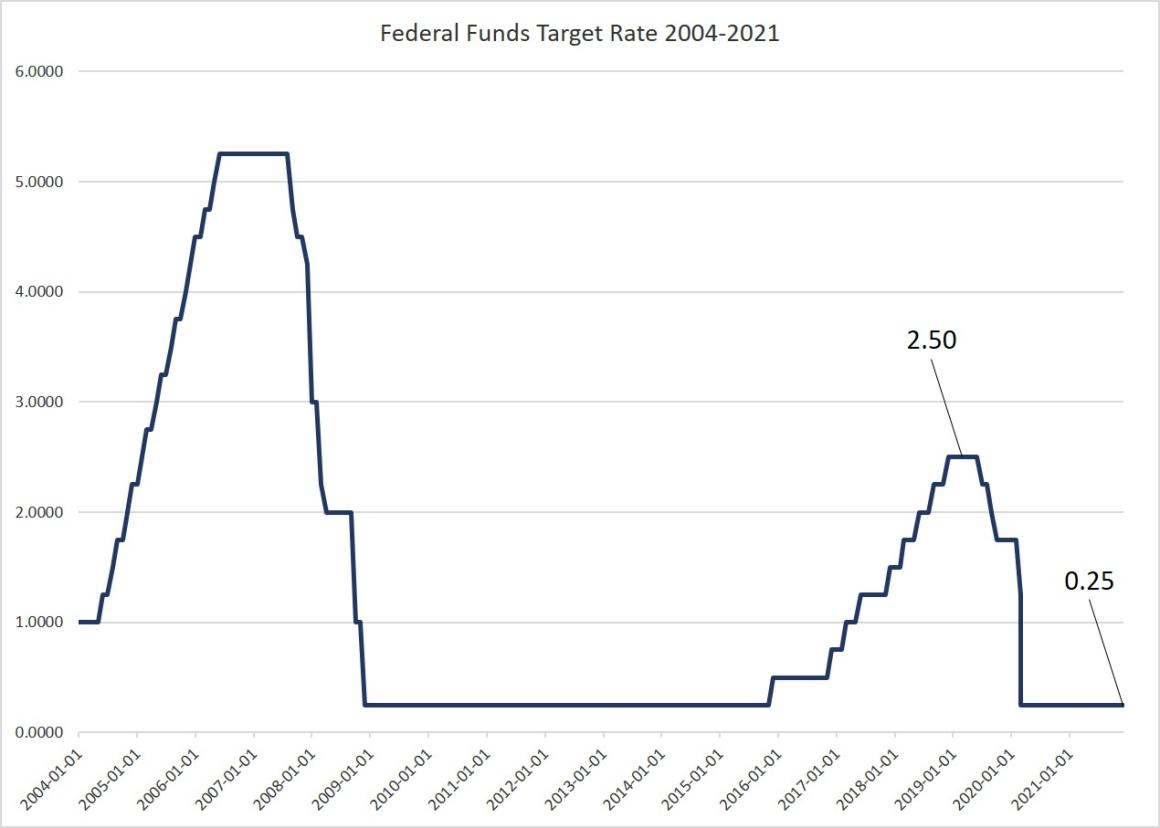

Second, the Fed plans to keep the target federal funds rate unchanged, at 0.25 percent. In other words, they plan to keep it where it’s been since March of 2020. The Fed is still on a crisis-stimulus footing as far as the target rate is concerned.

Third, the Fed will slow down its purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities. This is still just a slowdown, not an end, to purchases. And it certainly is not a sell-off of securities.

This is also a slightly sped-up version of what had been announced back in November when the Fed was still talking about buying up $70 billion per month in Treasurys and $40 billion per month in mortgage-backed securities. The January plan is for $40 billion and $20 billion, respectively. Yet total assets are still on their way to $9 trillion:

But what does the Fed have planned beyond January? The answer is: nothing that could be termed a real “pivot” or departure from the recent past.

On this, Robert Armstrong at the Financial Times perhaps has one of the savvier views. He concludes that Powell pivot "is a tactical tweak by [the] Fed that remains very dovish indeed.”

All this talk of the Fed’s turn away from claiming inflation is “transitory” misses the point, Armstrong points out. The term is gone, but the strategy at the Fed is still the same—which means they really still embrace "transitory" in practice. Supporters of the “Powell pivot” thesis point to the Fed’s so-called dot plot, which reputedly shows what Fed board members think is in store for future rate hikes. Rates in the latest dot plot ticked up slightly, but hardly in any way that suggests a big change. Armstrong continues:

It is true that the dot plot … unambiguously shows the Fed eyeing higher rates sooner. As telegraphed, the Fed is acknowledging short rates will need to rise somewhat to hedge against persistent inflation. That is evident in the 2022 and 2023 dots. But the median forecast for rates in 2024 nudged up only a bit, from 1.75 per cent to just over 2 per cent. The longer run dots have stayed the same. In the background is the very clear fact that the committee thinks, with a high level of unanimity, that a short raising cycle, topping out at 2.5 per cent, will ensure that inflation is transitory. The committee’s median projection is that personal consumption expenditure inflation in 2022 will be 2.6 per cent, and it is unanimous in thinking that in 2023 it will be barely above 2 per cent. That is, above target inflation will last about a year. Everybody, say it together now: transitory!

As we can see above, a target rate of 2.5 or 2.6 percent is not a departure from the past decade. During that time, the Fed only dared raise the target rate to 2.5 percent, and it was then that the US started to run into some serious signs of trouble such as the repo panic of late 2019.

The fact this is all very tame is reflected in the market itself. The Dow surged after Powell’s supposedly hawkish remarks on Wednesday. And the bond market has barely budged. A look at this week's yield curve shows as much: yes, some short-term yields are up, but in the longer term, all is calm. Almost nobody is actually expecting significant increases in yields beyond the next couple of quarters. And why should they? The Fed gives us no reason to think so.

And finally, there is the issue that rarely gets mentioned: the regime itself wants to keep borrowing at very low interest rates. Yet the federal government continues to add to the national debt at breakneck speed. That means a lot of deficit spending, which means the feds need to sell a lot of bonds, which leads to upward pressure on interest rates.

The US government isn’t alone in this, of course. Even the International Monetary Fund now warns about “interest rate risks,” noting that global debt surged hugely in 2020, with half of that being government borrowing. But all this means the Federal Reserve will have to continue to be on hand to buy up Treasurys if it’s necessary to keep federal interest payments low. So, we shouldn’t expect any dramatic moves toward higher rates or any sell-offs of Fed assets.

The real mystery now lies in how little tightening will be required to send the economy into a recession or the markets into a downward trend. For now, that remains a total unknown.Author:

Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!