Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR

Reprinted with permission Mises Institute Ryan McMaken

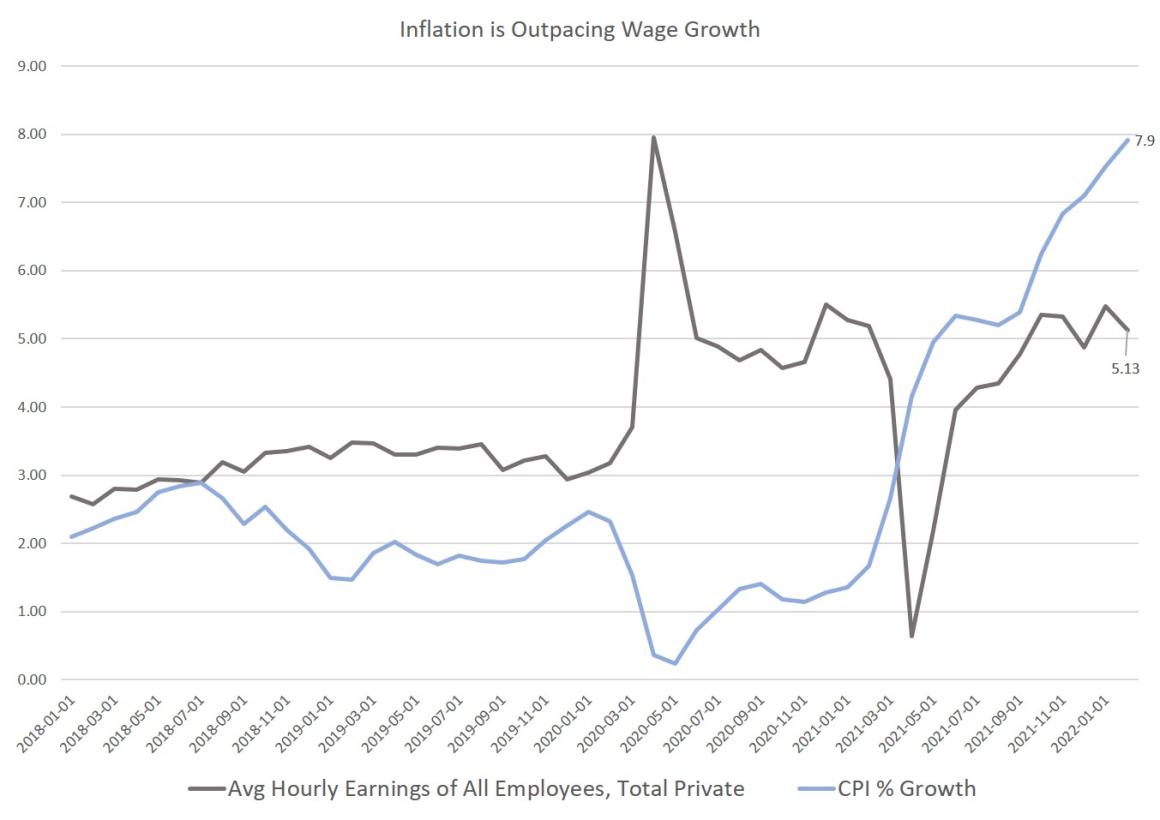

According to new data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, price inflation in February rose to the highest level recorded in more than forty years. According to the Consumer Price Index for February, year-over-year price inflation rose to 7.9 percent. It hasn't been that high since January 1982, when the growth rate was at 8.3 percent.

February's increase was up from January's year-over-year increase of 7.5 percent. And it was well up from February 2021's year-over-year increase of 1.7 percent.

A clear inflationary trend began in April 2021 when CPI growth hit the highest rate since 2008. Since then, CPI inflation has accelerated with year-over-year growth nearly doubling over the past 11 months from 4.2 percent to 7.9 percent.

For most of 2021, however, Federal reserve economists and their PhD-wielding allies in academia and the media insisted it was “transitory” and would soon dissipate. By late 2021, however, economists began to admit they were “surprised” and had no explanation for the inflation. (What one actually learns while obtaining a PhD in economics apparently has nothing to do with understanding money or prices.) Jerome Powell then declared that the Fed would prevent inflation from becoming “entrenched.”

Now, high level economists have changed their tune again with Janet Yellen admitting this week that “We’re likely to see another year in which 12-month inflation numbers remain very uncomfortably high.” Yellen had earlier predicted that CPI inflation would drop to around 3 percent, year over year, by the end of 2022.

Yellen was also careful to attempt political damage control by insinuating that price inflation is a result of uncertainty over the Russia-Ukraine war.

Never mind, of course, that the inflation surge began last year and that January’s CPI inflation rate was already near a 40-year high. The current crop of embargoes and bans on Russian oil imports implemented during March were not drivers of February’s continued inflation surge.

Few members of the public, however, will bother with these details, and this will benefit both the Fed and the administration. As far as the Fed is concerned, the important thing is to never, ever admit that price inflation is really being driven by more than a decade of galloping Fed-fueled monetary expansion (aka money printing). This was done largely at the behest of the White House and Congress to keep interest on the debt low and government spending high.

So, we can expect the administration to portray inflation as “Putin’s fault.” In a Friday speech to Democratic activists, Biden even claimed the high inflation rates are not due to “anything we did.” The tactic will no doubt work to convince many. But it’s unclear how many.

In any case, the Democrats—since they are assumed to be “in power”—will need some sort of scapegoat for inflation since it continues to eat into American’s earnings.

February’s numbers on average hourly earnings shows price inflation is outpacing earnings. As the graph shows, year over year earnings grew 5.13 percent, but price inflation grew 7.9 percent.

Source: BLS: Table B-3. Average hourly and weekly earnings of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls; Consumer Price Index.

Looking at this gap, we find that real earnings growth has been negative for the past eleven months. In other words, according to these official numbers, average works have now been getting poorer for nearly a year. In February, the gap was negative 2.8 percent, which was tied for the second-worst wage-inflation gap in more than a decade.

Source: BLS: Table B-3. Average hourly and weekly earnings of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls; Consumer Price Index.

Moreover, according to the Conference Board, US salaries are growing at a rate of approximately 3 percent this year—well below the 5-7 percent inflation rates experienced over the past year.

Combined with February's unemployment rate of 3.8 percent, February's inflation growth puts the US misery index at 11.7 percent. That's the highest level since June of 2020, and similar to the misery index levels experienced when the unemployment rate surged in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

In addition to CPI inflation, asset-price inflation will likely continue to be troublesome for consumers as well. For example, according to the Federal Housing and Finance Agency, home price growth has surged in recent months, with year-over-year growth now coming in at 17.8 percent.

Ever since it was forced to admit that price inflation is real and growing, it began to strike a pose as a hawkish institution committed to reining in inflation.

But when it has come to actual action, the Fed has spent many months talking about doing something while doing nothing other than very slowly cutting new purchases of bonds and mortgage-backed securities. These extremely limited and dainty strategies belie the Fed’s repeated claims that the economy is robust and that it the Fed plans strong action against inflation. It is far more likely that behind the scenes the Fed has been prepared to take anything it can get that can be used as an excuse for not raising interest rates or sizably reducing the size of the Fed’s portfolio. With the Ukraine war, the Fed may be get that excuse. This week, for instance, Karl Smith at Bloomberg has called for the Fed to "hit pause" on rate increases.

We should expect these calls to increase as the war continues to provoke uncertainty and as the economy continues to weaken. After all, Goldman has reduced its GDP forecast to 0.5 percent for the first quarter of fiscal year 2022, and sees mounting risk of recession for both the US and Europe.

The odds of the Fed chickening out and abandoning plans to cut monetary expansion have always been high. They’re even higher now that the war and a weakening economy will stoke inflation fears and another round of calls to “print the money” to prevent recession.

It’s all likely to add up to yet another political windfall for the Fed. In early 2020, the economic was weakening after more than a decade of remarkably slow economic growth and rising reliance on monetary expansion to prevent the implosion of Fed-created economic bubbles. But then covid happened, and the Fed blamed the disease for the economic collapse and inflation that followed. Now the war will provide yet another way for the Fed and its economists to claim they were doing a great job, and it would have all been a great success if not for the Russians.Author:

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor's degree in economics and a master's degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!