Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR, Truth Social

Reprinted with permission Mises Institute Ryan McMaken

It’s a sure bet that as the economy worsens, unemployment surges, foreclosures rise, defaults climb, and economic misery ensues, we’ll be told it’s all capitalism’s fault. The question one must ask, however, is, “What capitalism?”

The claim that “too much” capitalism drives every economic calamity is standard among anticapitalists on both the left and the right. They have many bullet points claiming government programs and government spending are everywhere retreating while free-market capitalism is experiencing a resurgence. This can be easily shown to be empirically false. Evidence can be found in everything from the continual flood of government regulations to rising per capita taxation and spending to the growing army of government employees. That’s all in the United States, mind you, the supposed headquarters of “free-market capitalism.” We might also point to how the US welfare state, including the immense amounts of government spending on healthcare and pensions, is on a par with European welfare states in terms of size. The supposed lack of social benefits programs in the US has long been a myth. The trend in spending, taxation, and regulation is unambiguously upward.

In recent years, though, one additional indictor of just how little capitalism is actually going on has surfaced: central banks around the world are buying up huge amounts of financial assets in order to subsidize certain industries, inflate prices, and generally manipulate the economy. This is certainly true of the American central bank, the Federal Reserve.

While the Fed has long bought government debt in its so-called open-market operations to manipulate the interest rate, wholesale buying of financial assets began in 2008. This included both US government Treasurys and—in a new development—private-sector mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). This was done to prop up banks and other firms that had bet on the lie that “home prices always go up.” The value of mortgage-backed securities was falling fast, so beginning in 2008, the Fed bought up MBSs to the tune of $1.7 trillion. That was all before covid.

The Fed attempted to begin selling off its portfolio in 2019, but by then the market was already so addicted to Fed money that the economy began to slow and a liquidity crisis in repos ensued. The covid panic was what prevented a full-blown recession in 2020: the federal government began a spree of deficit spending, and the Federal Reserve hoarded even larger amounts of assets, bringing totals to new record-breaking highs.

The MBS portfolio climbed to $2.7 trillion.

These sorts of volumes of assets are not an insignificant part of the overall market, either. Since 2020, the Fed’s MBS stockpile has equaled at least 20 percent of all the household mortgage debt in the United States. In early 2022, Fed-held MBS assets peaked at 24 percent of all US mortgage debt, but they still made up over 20 percent of the market as of late 2022.

One can only speculate as to the full extent to which markets are distorted by the central bank holding one-fifth of mortgage debt, but one thing is for sure: one cannot say that this is any sort of “capitalism” at work.

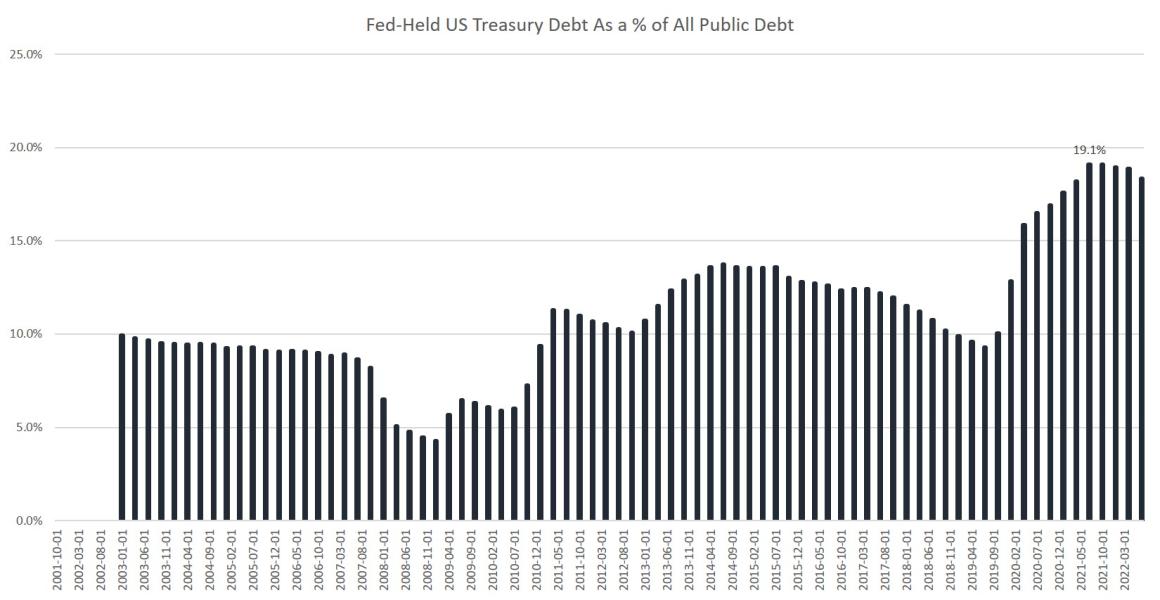

The story is similar with Treasury debt, and the timeline is largely the same as with the MBS assets. The Fed bought up about $2.5 trillion in US government bonds from 2008 to 2015. An attempt at scaling this back was aborted when the economy proved to be too fragile in late 2019. Then, the Fed gorged on Treasury debt in 2020 and 2021, bringing its government bonds total to nearly $6 trillion.

As a percentage, the Fed’s share of all Treasury debt has totaled more than 15 percent since 2020. It peaked at 19 percent in 2021. All foreign holders combined hold 33 percent of Treasury debt. This makes the Fed, by far, the largest domestic holder of US government debt: the Fed holds nearly 40 percent of all domestically held Treasury debt, putting it far ahead of entire sectors, such as mutual funds, which hold “only” around 22 percent of this debt.

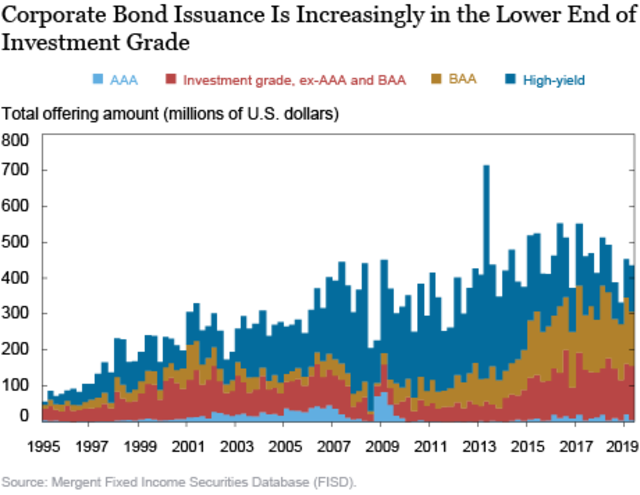

It’s also helpful to keep in mind that US Treasurys are a huge portion of the debt markets overall. For example, corporate debt in the US totals around $11 trillion. Even if we add this to the US Treasury debt, we still find that the Fed holds more than 10 percent of debt assets.

Of course, it would be absurd to call this situation anything resembling even “mostly” laissez-faire, let alone a free market. Imagine if a federal government agency—which is all the Fed is—owned 10 percent of all supermarkets or 10 percent of all Wal-Marts or 10 percent of all stocks. We would say that the agency in question possessed an enormous amount of power to move and manipulate markets as it willed.

That is where we are with these debt markets, and it’s become increasingly so since 2008.

Nor is the Fed the only federal agency involved. We might also point to how the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) have come to dominate the secondary markets in mortgages. For example, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae have been going on annual mortgage debt shopping sprees:

From 2009 to 2020, Fannie and Freddie’s annual share of the total MBS market averaged 70 percent. If we include Ginnie Mae securities, those that are backed by FHA [Federal Housing Administration] mortgages, the federal share of the MBS market averaged 92 percent per year.

Much of these MBSs, naturally, have ended up in the hands of the Fed.

So, now would be a great time to stop pretending that the financial sectors are “free market” or that price inflation and cost-of-living surges are somehow all the fault of “capitalism.” Federal agencies are the biggest players here, and their role is to manipulate markets to achieve centrally planned government goals. Private markets are growing more irrelevant every day.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor's degree in economics and a master's degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Breaking Away: The Case of Secession, Radical Decentralization, and Smaller Polities and Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!