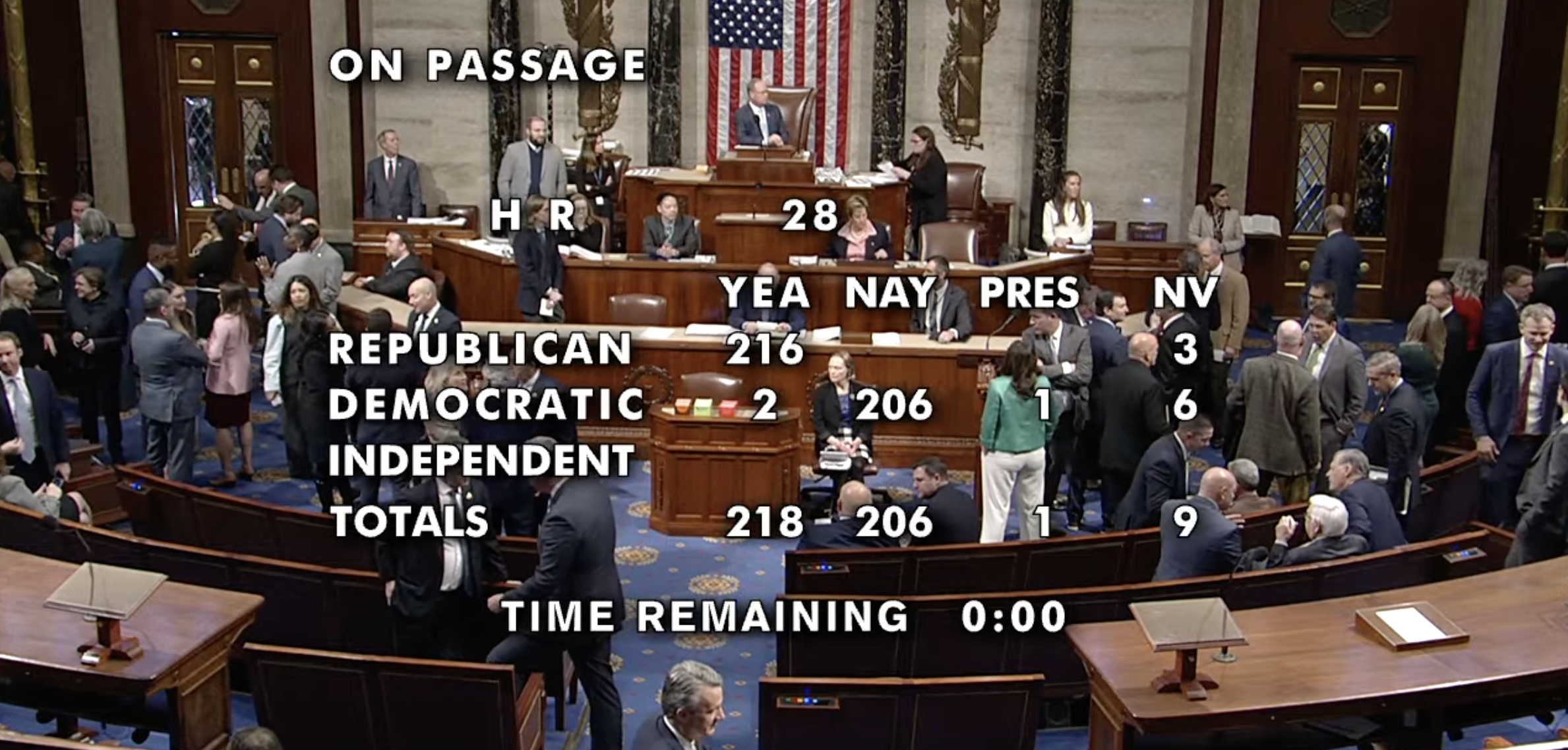

What does it take to get elected to the presidency these days? That depends on the strength of your ideas plus the amount of money you have to disseminate them (and how effectively you do so). Donald Trump was famously outspent in 2016 by Hillary Clinton, as reported by the Guardian:

Over the course of the primary and general elections the Trump campaign raised about $340m including $66m out of his own pocket. The Clinton campaign, which maintained a longer and more concerted fundraising focus, brought in about $581m.

Trump is the exception to many rules. Wealthy yet relatable, he is that rarest of candidates, who, regardless of net worth, exists within the system, yet outside of the beltway.

So money isn't everything, but it is utterly critical. Take Joe Biden's chicken-or-egg dilemma: despite his unmatched familiarity and crucial ability to attract the black vote, despite still polling in the top two in most national polls, he's falling fast.

Biden's inability to raise money is due in part to scandal, but it's also due to a poor ground game and lackluster debate performances. Yes, the average voter finally knows about son Hunter's Ukraine and China involvement, so new donors are more skittish, but Biden doesn't have the skills to raise the funds necessary to buy narrative-countering ads.

In the end, the inability to raise money reflects poorly on the candidate or his campaign. For Biden, so strong out of the gate, it was a decline in both personal and team reputation that led to empty coffers.

Enter Billionaires

The late Ross Perot was the first billionaire candidate for presidential office. Perot was able to make a sizable splash in 1992 when he brought his personal fortune to bear on the presidential election. He garnered 19% of the popular vote on a business-oriented, anti-deficit message coupled with no-nonsense delivery. He died last year worth over $4 billion.

Since Perot, we've seen several high net worth candidates able to dip into their own pockets in case donors dried up. John Edwards, John Kerry, Steve Forbes, John Huntsman, and Mitt Romney are all worth tens or hundreds of millions.

Of course, Donald Trump was the second billionaire to run. Keep in mind, there are only 2,200 billionaires in the world on any given day. Roughly 600 of those are U.S. residents. It's a fairly small club.

Why bother drawing the billionaire distinction? Because billionaires are able to buy entire newspapers on a whim, as Jeff Bezos has done with his 2019 purchase of the Washington Post. Instant publicity, custom-built narratives. Moreover, billionaires can spend multiple hundreds of times more than their closest rivals, even the very rich.

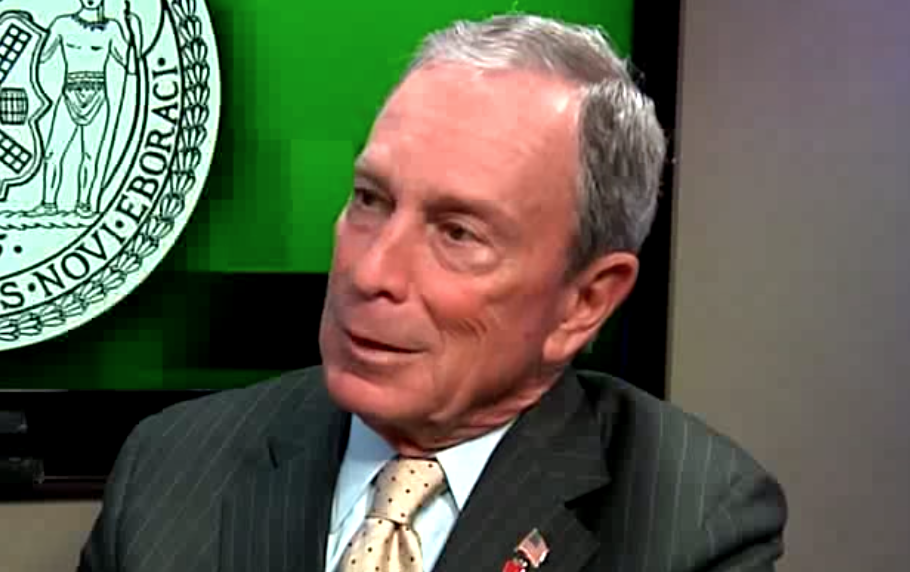

This year, Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg are running against Trump. Three billionaires in one race.

The implications are easy enough to see. Do we allow our elections to become spend-fests where hyper-rich candidates consume every moment of ad time until voters are putty in their hands? If you think that's an exaggeration, that voters don't react to ads, consider Bloomberg.

The former NYC mayor is polling at 12% in the latest Economist/YouGov national poll. 12 points! That's ahead of Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar. Without a single debate performance, or indeed, any platform at all. He is what voters imagine him to be, largely unknown beyond New York. On ad money alone, he's in the biggest race in the country. He stands poised to unleash a media barrage the likes of which we have never seen leading up to Super Tuesday on March 3rd.

Bloomberg has already spent $350 million, and is reportedly willing to spend $1 billion. If he isn't chosen, he can throw his support behind the candidate of his choice. King or kingmaker, he will be the single most influential individual in the 2020 election process.

That's too much power for one citizen to wield in a national election.

Lest we become complicit in rule by oligarchs, a cap must be put in place for personal spending in national elections. Bloomberg's net worth is $60 billion. Spending a billion (or three, or ten) won't so much as dent any aspect of his life. Other candidates not only struggle to raise funds, but perversely, donors will be less likely to give to someone going against a Goliath like a Bloomberg or a Bezos.

The final ugly aspect of too much money in politics: the invasion of our personal lives that billions of dollars can inflict. If you live in swing state, your TV, radio, mailbox, email, texts, and social media stand to be dominated by one individual. It's beyond any notion of canvassing as conceived by laws made in the analog era. Such a many-headed assault lacks all proportion or propriety.

Proposed solution: an average of the last three campaign outlays by both major parties as a cap, adjusted for inflation and other exogenous factors, with regularly scheduled congressional review.

It's a starting point. A first step we will all regret not taking, lest we allow the presidency to turn into an office for the highest bidder.

Except, any limit would limit my ability to speak, individually or in a group of like-minded persons. The Supreme Court rightfully says such limits are unconstitutional. The danger of oligarchy is present — billionaires or Google-ites. But, spending restrictions are not the way. What’s Is Plan B?

The basic underlying assumption being made is that voters are persuaded to vote strictly by the volume of advertising for a candidate. The American public is continuously bombarded by advertising extolling the virtues of everything. Just life experience teaches us that ads are always overstating the benefits of whatever is advertised. A healthy skepticism is the result.

Political advertising is subjected to this same skepticism, both positive and negative ads. I also suspect that there is a limit to effective advertising in politics - or at least a point of diminishing returns. There may also be a a point of negative return where the candidate is considered to be overdoing it or just becomes annoying.

The potential of there being a natural limit (which will increase with the rise in costs) beyond which extra expenditures actually hurt a candidate exists. If Bloomberg makes good on his promise to spend money like he is all the way through election day we may actually have proof of this.