Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR, Truth Social

Reprinted with permission Mises Institute Ryan McMaken

Most commentary on the Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization—which overturns Roe v. Wade—has focused on the decision's effect on the legality of abortion in various states. That's an important issue. It may be, however, that the Dobbs decision's effect on political decentralization in the United States is a far bigger deal.

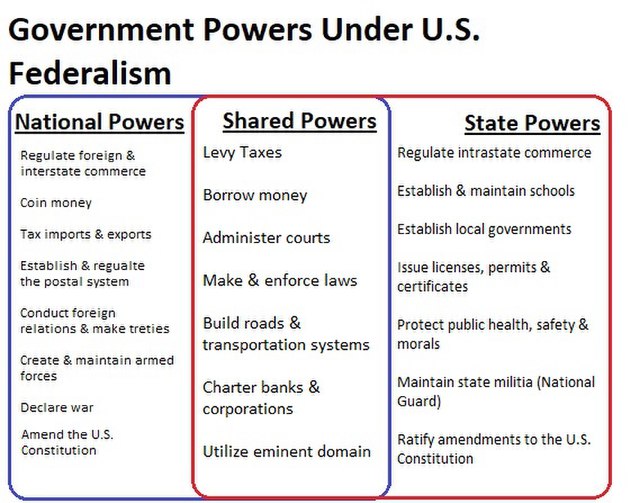

After all, the ruling isn't so much about abortion as it is about the federal government's role in abortion. State governments are free to make abortion 100 percent legal within their own borders. Some states have already done so. The court's ruling limits only the federal government's prerogatives over abortion law, and this has the potential to lead to many other limitations on federal power as well. In this way, Dobbs is a victory for those seeking to limit federal power.

The decentralization is all to the good, and there's nothing novel about it. Historically, state laws in the US have varied broadly on a variety of topics from alcohol consumption to divorce. This was also true of abortion before Roe v. Wade.

Moreover, decentralizing abortion policy in this way actually works to defuse national conflict. This is becoming even more important as cultural divides in the United States are clearly accelerating and become more entrenched. Rather than fight with increasing alarm and aggression over who controls the federal government—and thus who imposes the winner's preferences on everyone else—people in different states will have more choices in choosing whether to live under proabortion or antiabortion regimes. In other words, decentralization forces policymakers to behave as they should in a confederation of states: they must tolerate people doing things differently across state lines. This will be essential in avoiding disaster, and laissez-faire liberals (i.e., "classical liberals") have long supported decentralization as a key in avoiding dangerous political conflicts. Ludwig von Mises, for example, supported decentralization because, as he put it, it "is the only feasible and effective way of preventing revolutions and civil ... wars."

Law has never been uniform across state lines in the United States, although this was not for a lack of trying on the part of the federal government. As the power of the federal government grew throughout the twentieth century, the central government repeatedly sought to make policy uniform and put it under the control of federal courts and regulatory agencies. Prior to Roe v. Wade, abortion was a state and local matter only. Before the drug war, the federal government did not dictate to states what plants they should let their citizens consume. Before the Volstead Act, "dry" states and "wet" states had far different policies on alcohol sales. Some states had lenient divorce laws. Some did not. Some states allowed gambling. Even immigration was once the domain of state government. Although some federal law enforcement agents existed in the nineteenth century, "law and order" was overwhelmingly a state and local matter prior to the rise of agencies like the FBI.

The cumulative effect of making all these areas the prerogative of federal regulators, agents, and courts has been to convince many Americans that the United States government ought to federalize most areas of daily life. In the modern way of thinking, only less important or trivial matters are to be left up to the state and local governments. For many Americans, they learned to just think that it was abnormal for the state next door to have different gun policies or drug policies than one's home state.

In the past decade, this impulse to intervene in neighboring states has been highlighted by the de facto end of nationwide marijuana prohibition in the United States. Beginning in 2012 with Colorado and Washington State, recreational marijuana use has become essentially legal in nearly two dozen US states. This means a resident of one state can travel to a neighboring state to consume a drug that is illegal in his or her home state. Some state governments have a hard time dealing with this. Politicians in antimarijuana states complained that their citizens had too much access to prohibited substances. Not surprisingly, attorneys general in Nebraska and Oklahoma sued Colorado in federal court in an attempt to force Colorado to reimpose marijuana prohibition on its citizens. Fortunately, these lawsuits—which if successful would have greatly expanded federal power over states—failed.

Alcohol prohibition grew out of the same desire to force some states' preferences on all other states. In 1917, only twenty-seven states embraced statewide prohibition. It took a constitutional amendment to impose prohibition on all the rest.

Moreover, laws governing the purchase and carry of firearms vary broadly from state to state, with "constitutional carry" allowing permitless carry in some states. Some states allow for private gun sales without any background checks. Other states greatly restrict these activities. Naturally, policy makers who oppose the freedom to carry firearms have sought for many decades to impose uniform gun policy nationwide.

The most notorious case of using the federal government to impose nationwide uniformity is likely the Fugitive Slave Acts (passed in 1793 and 1850). Contrary to the myth that slave owners hated a strong federal government and wanted only local control, slave drivers enthusiastically and repeatedly invoked the federal fugitive slave laws. This was done in order to force Northern governments to cooperate with Southern states in kidnapping runaway slaves and returning them to their "owners." The Dred Scott decision extended federal protections of slavery even further, and the ruling allowed many slave owners to argue they could even take their slaves into nonslave states and territories, regardless of state and local laws prohibiting slavery.

Many abolitionists refused to acknowledge federal prerogatives and actively opposed federal agents who attempted to enforce federal laws extending slavery beyond the slave states. Some Northern governments explicitly refused to cooperate with the Fugitive Slave Acts. So successful were these efforts to undermine federal law that South Carolina secessionists listed the failure of federal slave laws as a reason for secession in 1860. Slavery advocates were enraged by the idea that their neighbors in other states weren't being forced to help prop up the slave system.

In all of these cases, the perceived "answer" offered by proponents of legal uniformity was to bring in the federal government to force people in state A to do the bidding of people in state B. Thanks to the overturning of Roe, however, many states are moving in exactly the opposite direction.

Some states have moved toward prohibiting abortion within their own borders. But proabortion states are also taking some key legal steps toward further decentralizing policy. Policy makers in Massachusetts have moved to protect the state's citizens from extradition to antiabortion states for abortion-related crimes. The state's governor also signed an executive order prohibiting the state's agencies "from assisting another state's investigation into a person or entity" for abortion-related activities. New York's governor has signed legislation "that shields [abortion] providers and patients from civil liability" in abortion-related claims. The message here: "Those laws in antiabortion states have no power here."

This is the way the system was designed to work. People can choose to live in state A, where abortion is illegal. But should some of those people travel to state B to get an abortion, state B ought to be under no obligation to help state A enforce its laws either inside or outside the state. To demand anything more than this inevitably ends up involving the federal government to impose new obligations on every state. (This strategy of centralizing power should not be confused with trying to directly change laws within those states. It is, of course, a good thing to pressure governments to end unjust laws from within, but such efforts are totally different than calling in the federal government to end abortion by federal fiat.)

As we have seen with abortion, slavery, drugs, and guns, when the feds are involved, every national election ends up being a referendum on whatever issue is deemed so important that the federal government must impose one way of doing things on everyone. This only makes national politics even more nasty.

The end of Roe v. Wade may end up emphasizing the political and cultural divisions in America by forcing many Americans to recognize that the United States is not one place. It is many places. This is not a problem, however, if we relearn that rather than employ federal coercion to "solve" the world's problems, it's perhaps better to tolerate others doing things differently in other parts of the world. On the other hand, if Americans can't shake the idea that the regime must force one way of life on everyone, we can expect national political divides to grow ever more bitter. Author:

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor's degree in economics and a master's degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!

As long as you keep the slavery issue alive it will be a problem.

Let it die a well deserved death.