Just two weeks after U.S. oil production posted yet another record, this time hitting 12.3 million barrels per day (bpd) to solidify the country’s hold as the world’s top crude producer, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) said that U.S. oil output from seven major shale formations is expected to rise by about 83,000 bpd in June to a fresh peak of about 8.49 million bpd. Russia, for its part, is the world’s second largest crude oil producer, followed by OPEC de facto leader Saudi Arabia which also maintains its hold as the top global crude oil exporter.

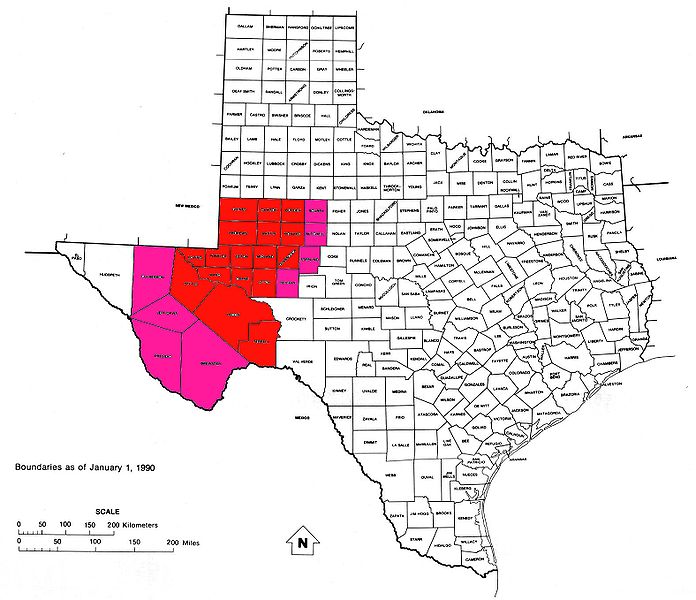

The uptick in U.S. shale production continues to come from two major shale formations, the prolific Permian Basin in west Texas and southeast New Mexico, and the Bakken region in North Dakota. Output in the Permian is expected to climb by 56,000 bpd to a new record of about 4.17 million bpd in June, according to the EIA, marking the largest increase in the Permian since February. Production in the Bakken is expected to increase by 16,000 bpd to a record of 1.42 million bpd. However, production in the Eagle Ford in south Texas near the Mexican border production is projected to drop slightly by around 942 bpd to 1.43 million bpd.

Significant take-aways

There are significant take-aways from the EIA disclosure. Production in these three major shale formations have helped pushed the U.S. past both Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest global oil producer, a slot that the U.S. lost in the early 1970s as conventional oil production in Texas started trending downward at the same time that Saudi Arabian production increased. It was also during this time amid increased U.S. oil consumption and declining crude production that the country lost its role as global oil markets swing producer to Saudi Arabia, a development that roiled global oil market for decades, created foundational geopolitical shifts not only in the middle-east but worldwide and saw the U.S. and most of its Western allies and Japan dependant on geopolitically charged middle-eastern crude for half a century.

U.S. oil weapon

Now however, the U.S. has revolutionized global oil markets and shifted considerable power back into the hands of both American oil producers and even Washington that has recently indicated it could use oil and gas exports as a geopolitical weapon. In March, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged the oil industry to work with the Trump administration to promote U.S. foreign policy interests, especially in Asia and in Europe, and to punish what he called “bad actors” on the world stage, adding that America’s new-found shale oil and natural gas abundance would “strengthen our hand in foreign policy.” He said that the U.S. oil-and-gas export boom had given the U.S. the ability to meet energy demand once satisfied by its geopolitical rivals. He made his comments at IHS Markit’s CERAWeek conference in Houston, where U.S. oil and gas executives, energy players and OPEC officials usually gather annually to discuss global energy development

This was the first time, in at least recent history, that U.S. officials have considered using oil production and exports for geopolitical advantage. One of the last times the country had such oil production clout dates back to the years just before World War II when the U.S. discontinued oil exports to Japan for its military adventurism in Asia. Consequently, this was one of the mitigating factors that provoked Japan to attack Pearl Harbor in 1941. Moreover, Pompeo's comments can be viewed as a reversal from the so-called oil weapon that Arab producers have used on the U.S. and its western allies for decades, including both the unsuccessful 1967 Arab oil embargo and the 1973 Arab oil embargo that brought the U.S. and its allies to their knees, driving up the price of oil four-fold and contributing to severe economic headwinds for the West and a geopolitical and economic shift that still persists in large part to the present.

Personally, as an American, I would just as soon we meet our own needs and perhaps those of near neighbors in the Western hemisphere and conserved our resources so we remain energy independent for a very long time. It made no sense sending tens of billions of dollars to areas filled with people who hated us (AKA the Middle East) every year and then have them divert it to fund Islamofascist terrorism. America should just build our own economy and military strength to dominant levels but for the most part let the people who want to live a 7th century existence or waste their economic strength on fruitless local wars just squander their strength. We do not need to dissipate our strength by trying to nation build in countries eager to live primitive tribal existences. We do need to control the underseas, seas, skies, space and cyberspace to protect our homeland and to be in a position, as Britain did for centuries, to deny water-borne trade to would be Eurasian hegemonies like China, shutting down their economies if necessary (since without trade China would collapse in a year). It is our job to make democracy safe and effective, our society just in our country but it is not within our power or responsibility to force people who do not want freedom or rule of law or free market economics or technological and scientific progress to embrace it - we should offer a rational affordable level of help to those who do want these things but let those who do not just rot in their backwardness.