Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR, Truth Social

Reprinted with permission Mises Institute Ryan McMaken

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed on Friday and was shut down by regulators. It was the second-largest failure in US history and the first since the global financial crisis. Almost immediately, the calls for bailouts started to come in. (Since Friday, First Republic Bank has failed, and many other banks are facing collapse.)

In fact, on March 9, even before SVB failed, billionaire investor Bill Ackman took to Twitter to insist a federal “bailout should be considered” if the private sector could not save the bank. Hours after SVB officially failed, Ackman was still at it, and in a 646-word panicky screed, he demanded that the federal government “guarantee SVB deposits” and essentially backstop the entire banking industry to keep failing, inefficient, and poorly managed banks afloat.

Now, many readers might be saying to themselves, “I thought bank deposits were insured!” That, of course, is correct, but deposits are only legislatively insured up to $250,000 by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Given that most normal people keep less than this in their bank accounts, that means the majority of bank users are not going to lose any of their money should their banks fail. Moreover, it is extremely easy to acquire deposit insurance on much more than $250,000 by simply keeping money at more than one bank. That $250,000 limit applies to the deposits at each bank where a depositor keeps funds. For customers with high liquidity needs, the financial sector offers tools for dealing with the risk of exceeding FDIC limits.

In an illustration of the laziness and arrogance that so characterizes our modern financial class, however, many of the wealthiest depositors at Silicon Valley Bank couldn’t be bothered with managing their deposits, and they essentially ignored the deposit-insurance rules that even a ten-year-old understands when opening his first bank account.

As a result, many venture capitalists and other wealthy SVB customers stand to a lot of money. At least, they stood to lose a lot of money before Sunday evening, when the Federal Reserve announced its new “Bank Term Funding Program” (BTFP), which promises to flood the banking system with new money and shore up the personal finances of wealthy depositors.

This is part of a two-pronged effort to both make banks appear more financially sound, and to greatly expand FDIC payouts to depositors who have their funds in these banks.

The official propaganda coming out of the administration, and from the usual Fed fanboys, is that none of this is a bailout. That’s a lie. The new steps being taken by the Fed and by the Treasury Department's FDIC are indeed ultimately bailouts for billionaires and other wealthy depositors. Moreover, this new program will require at least a partial return of quantitative easing. There’s no way to guarantee such huge sums of money without having to fall back on inflationary monetary policy yet again. This also means price inflation won’t be going away. Here is why.

The first prong of the bailout plan is to use extremely low-cost loans to shovel more money at banks in order to make them look more financially sound. The idea here is to head off depositor panics over uninsured deposits before they start. The first indication that this scheme is a bailout comes from the text of the press release on the creation of the BTFP. It states that the new program will be

offering loans of up to one year in length to banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions pledging U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities [MBS], and other qualifying assets as collateral. These assets will be valued at par. The BTFP will be an additional source of liquidity against high-quality securities, eliminating an institution’s need to quickly sell those securities in times of stress.

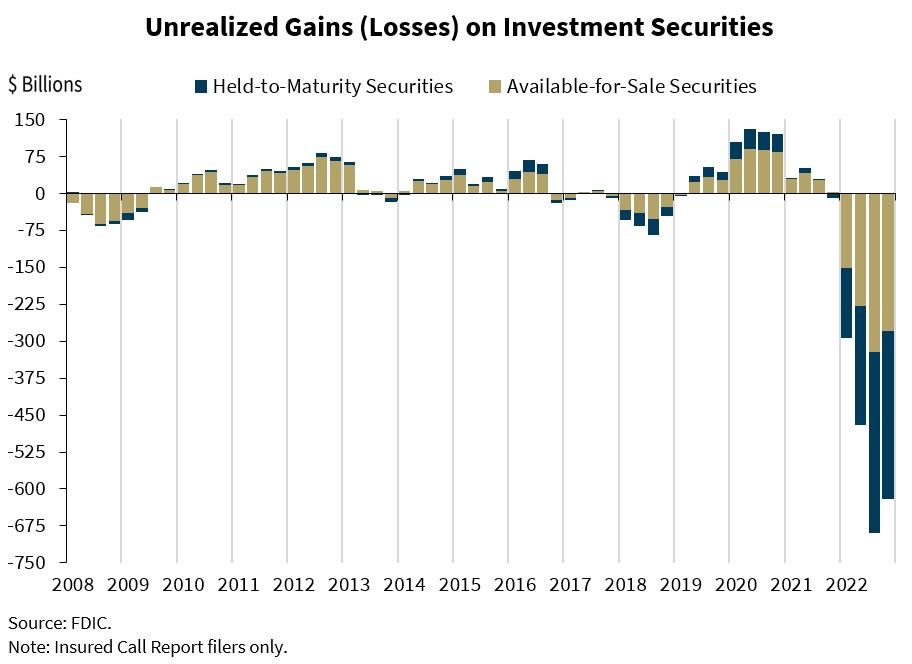

The key phrase is “These assets will be valued at par.” That’s important because these banks are facing huge unrealized losses, many stemming from losses on assets whose market prices plummeted as interest rates rose. Part of the reason these banks are in trouble is because their assets are no longer worth anywhere near par value in the marketplace:

Yet, the Fed has decided to simply declare that banks' assets sit at par value and thus far more valuable than is really the case. It will let banks use these assets as collateral at the imaginary (higher) prices.

Moreover, the terms of the BTFP loans reiterate how these are loans designed to hand money to banks for little in return. According to the Fed, “there are no fees associated with the Programs” and there is no penalty for prepayment. Foreign banks are also eligible, by the way. And, of course, “the Department of the Treasury . . . [will] provide $25 billion as credit protection.” If history is any guide, we can expect that Treasury backstop to get a lot bigger. If and when some of these banks default on the loans, the collateral won’t come close to covering the value of the loans. The banks are essentially getting free money.

[Read More: "Why the Fed Is Bankrupt and Why That Means More Inflation" by Ryan McMaken]

Where will the money to provide these loans come from? It will be printed, of course. The Fed is already bankrupt and has no extra money lying around. The Fed can’t just start selling off its $8.5 trillion hoard of Treasurys and MBS to get cash. That would drive down the prices of those assets even further, and this would make balance sheets at banks—who also own Treasurys and MBS—even worse. So, new loans and guarantees will have to come from new money. Another phrase for that is "monetary inflation."

The second prong of the bailout is the FDIC's promise to cover all depositors at troubled banks, rather than just those with deposits up to the usual limit. The not-a-bailout narrative claims that the new promised expansion of insurance will all be funded by FDIC fees and imposes no costs on taxpayers. "The banks will pay for it," we are told.

That’s not how it will actually work. In this three-minute video, Peter St. Onge explains the real problem:

St. Onge notes that the FDIC fund available for backstopping deposits is less than $130 billion. Yet deposits in US banks total approximately $22 trillion. The FDIC fund is equal to about 0.6 percent of all the deposits. And it appears that even at the banks with the highest proportion of FDIC-covered accounts, only 42 percent of deposits are covered by insurance. So, clearly, extending FDIC coverage to all deposits means the FDIC will have nowhere near the funds it needs to cover potential depositor losses. The FDIC was never intended to insure rich people with deposits well in excess of FDIC insurance maximums. Yet that is exactly what is now happening.

When the FDIC runs out of money, what happens? The FDIC runs to the US Treasury to get a bailout. Where does the money to bail out the FDIC come from? It comes either from current tax revenues or from borrowed money. Either way, the taxpayers are on the hook. Moreover, if the Fed intervenes to buy up some of that new government debt—to keep federal interest obligations low, of course—then taxpayers will also pay via the inflation tax.

[Read More: "How the Fed Is Enabling Congress's Trillion-Dollar Deficits" by Ryan McMaken]

When we consider all this, we can see how the grift works: the Fed or the Treasury Department creates a “fund” and claims that it will be financed by fees and other nontax revenue sources. Thus, when the FDIC or the Fed rush to bail out banks, the politicians can claim the taxpayers will pay nothing. That is only true if the programs themselves receive no backstopping from the Treasury or from monetary inflation. But if we’ve learned anything since 2008, it’s that these programs all enjoy implicit guarantees of taxpayer backing, and that any “caps” on these amounts can be increased at any time.

In any case, the ordinary taxpayer will certainly feel the pain in terms of ongoing price inflation. Current bailout efforts are inflationary and are thoroughly opposed to the Federal Reserve’s recent attempts at “quantitative tightening.” The whole point of the bailouts, after all, is to loosen financial conditions for banks. So the Fed will almost certainly be backing off whatever it had planned in terms of raising the target interest rate and reducing its portfolio at the next Federal Open Market Committee meeting. Now the Fed will be looking at whatever strategy it can find to increase the flow of dollars to banks, and that will mean more money creation, even if the Fed’s official position remains ostensibly hawkish. Put another way, get ready for more entrenched price inflation. But don’t forget that the primary focus of all of this is to bail out wealthy depositors and bankers. On top of it all, there’s no guarantee that it will even work. There’s a reason the financial technocrats are in panic mode. They don’t know what will happen next.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor's degree in economics and a master's degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Breaking Away: The Case of Secession, Radical Decentralization, and Smaller Polities and Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!