In 2018, U.S. natural gas production reached a record high, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) said on Thursday. Natural gas production in the country grew by 10 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in 2018, an 11% increase from 2017. The growth was the largest annual increase in production on record, reaching a record high for the second consecutive year.

U.S. natural gas gross withdrawals increased every month during 2018 except in June, ultimately reaching a record monthly high of 107.8 Bcf/d in December 2018, the EIA said.

So-called marketed natural gas production and dry natural gas production also hit monthly record highs of 95 Bcf/d and 88.6 Bcf/d, respectively, in December 2018. Marketed production reflects gross withdrawals less natural gas used for repressuring wells, quantities vented or flared, and nonhydrocarbon gases removed in treating or processing operations. Dry natural gas is consumer-grade natural gas, or marketed production less extraction losses.

U.S. gas exports, both pipeline gas and seaborne liquified natural gas (LNG), increased in lockstep amid gas production highs. This year, U.S. LNG exports continue to increase as Gulf Coast terminals ramp up production, flooding an already saturated global market with prices for spot trading of the super-cooled fuel reaching multi-year lows amid the supply overhang.

Moreover, in 2018 the U.S. shipped/exported natural gas by pipeline more than it imported by pipeline for the first time in 20 years. The EIA also projects that for 2019 this trend will continue.

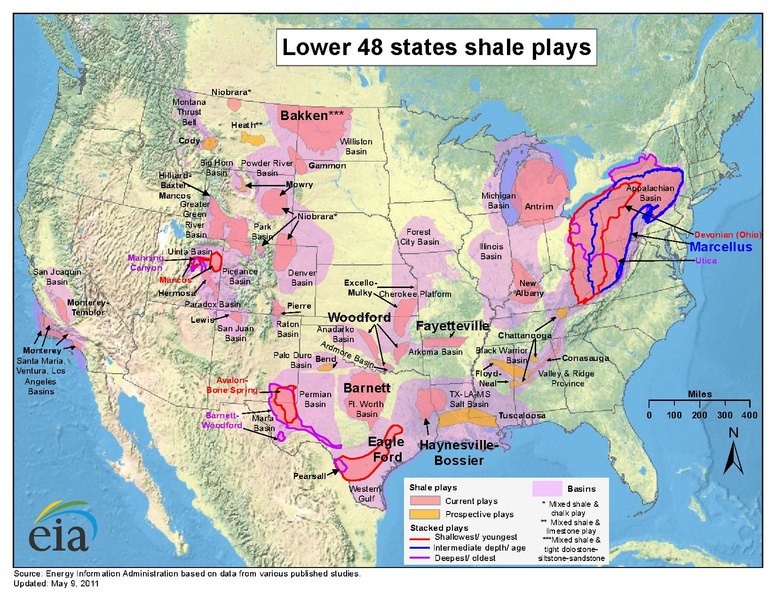

The Appalachian region remained the largest natural gas-producing region in the country, according to the EIA. Appalachian natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica/Point Pleasant shales of Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania continued to grow, with gross withdrawals increasing from 24.2 Bcf/d in 2017 to 28.5 Bcf/d in 2018. Ohio saw the largest percentage increase in gross withdrawals of natural gas, up 34%, in 2018 to 6.5 Bcf/d.

Texas develops a gas problem

Texas, home to the lion’s share of the country’s uptick in shale oil production, also saw the largest total volumetric gain in gross gas withdrawals in 2018, increasing to 24.1 Bcf/d, up from the state’s 2017 production of 21.9 Bcf/d.

The Lone Star state’s increase in natural gas production is mainly due to Permian Basin and Haynesville Shale formation development. In 2018, production in the Permian increased by 2.7 Bcf/d, or 32%, while production in the Haynesville increased by 2.2 Bcf/d, or 34%.

The Permian basin, a power house of both oil and gas production, is about 250 miles wide and 300 miles long, spanning parts of west Texas and southeastern New Mexico. It includes the highly-prolific Delaware and Midland sub-basins.

By the end of last year, it had produced more than 33 billion barrels of oil, along with 118 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas. This production accounted for a whopping 20% of all U.S. crude oil production and 7% of U.S. dry natural gas production.

According to analytics and data provider IHS Markit, the Permian shale play holds an estimated 60-70 billion barrels of recoverable crude oil. To put that in perspective, that’s enough to feed all the U.S. refineries for a decade plus. Rystad Energy estimates for the Permian are even higher, placing them at some 100 billion barrels of recoverable oil resources.

However, there are also systemic problems at the Permian. Since Permian fields are shale plays, the majority of its oil production is derived in the first year, in some cases as much as 60%-70%. As oil fields quickly deplete, energy players encounter more gas, which they either have to flare (burn off) or pay to have hauled away.

In the Midland portion of the Permian, the average well produces about 2,000 cubic feet of gas for each barrel of oil in its first year, according to Tom Loughrey, a former hedge fund manager who started shale data company Friezo Loughrey Oil Well Partners LLC, (FLOW), Blomberg said in a report yesterday.

“Shale wells are notorious for their steep output declines; however, that decline is more severe for oil than for gas and NGLs [natural gas liquids]. Gas and NGL production continues for much longer, increasing the gas-to-oil ratio of most U.S. shale plays,” he said.

Meanwhile, Permian producers are already reportedly flaring gas at record levels. The Texas Railroad Commission granted almost 6,000 permits allowing companies to flare or vent natural gas this year. That’s more than 40 times as many permits granted at the start of the supply boom a decade ago, Bloomberg added.

Compounding the problem, shale developers in the Permian need will have to drill even more wills just to maintain current production levels. IHS Markit said earlier this month that the base decline rate, or the rate at which production will fall through the year, has “increased dramatically” for more than 150,000 producing oil and gas wells in the Permian Basin.

Suffice it to say, more pipeline infrastructure is needed to haul away the gas and thereby reduce excessive flaring - a problem that has plagued the U.S. shale industry since its inception nearly a decade ago. Unfortunately, development is still failing to keep up with production. Until then, more gas will be flared, creating both an environmental quandary as well as tarnishing an otherwise stellar story of U.S. oil and gas production renaissance.

Subscribe to our evening newsletter to stay informed during these challenging times!!